In a discussion of the character of an individual who was born over 400 years ago one must consider the various sources of information available. The primary record includes the person’s own words as in an autobiography or a diary or poetry. The words of individuals who were near the subject such as their biographer, relatives or friends. The record of the subject’s enemies or opponents who left a record that included the other side of the story. The secondary record of historians who wrote shortly after the events, when there was still strong feelings both pro and con as to the justice of the subjects actions. History written with the tincture of time when the emotions around the events have been largely forgotten and the effects of the subject’s actions can be analyzed in light of their impact on those involved from a more neutral point of view can be considered a tertiary record.

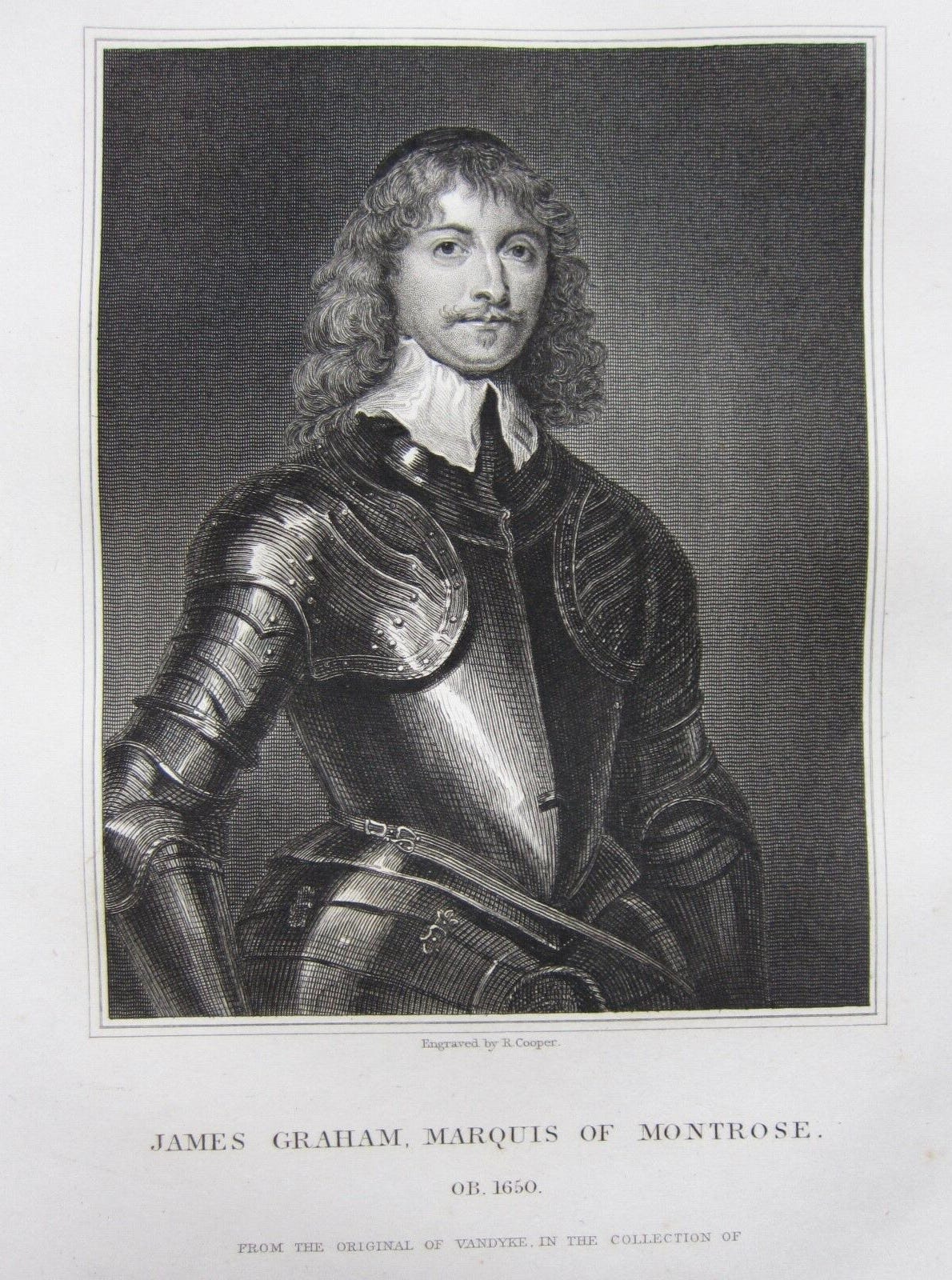

James Graham was the only son of John Graham, the 4Th Earl of Montrose, who lost his wife Lady Margaret Ruthven when James was 6 years old. His two elder sisters may have taken over the role of mother because it is recorded that he was always welcome at their homes. (1) His sister, Margaret Graham had married Lord Napier who later became one of his guardians, a close friend and loyal supporter. He had an early love of horses and riding and the bills of the Aberruthven blacksmith bear testimony to this. (2) James also enjoyed hunting and became proficient by hunting the wild goats and roebuck of Loch Lomondside.

Thanks for reading The Seanchaidh! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

✓

At the age of 12 his father sent him to Glasgow with Master William Forrett to prepare for college. James lived in the house of Sir George Elphinstone, the Lord Justice Clerk, that may have been one of the old manses of the Cathedral. The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland shows the house to be on Drygate Street, which connects to Cathedral Street and is short one third of a mile walk from the Cathedral itself. The Royal Commission records show that at a later date the Duke of Montrose owned the property but there is no evidence of the Earl owning it in 1624.(3)

Montrose’s life changed dramatically upon the death of his father in 1626, he became the Chief of the Grahams but as a minor of 14 he was placed under the watchful eye of the sub chiefs of the clan. He was enrolled at St. Salvator’s College, St. Andrews. His love of archery revealed itself when in his second year he won the silver medal for archery and held it until he left college.

He is noted to have enjoyed golf, hawking, riding and hunting during his years at St. Salvator’s. Little is known of his academic record at St. Salvator’s except that he particularly enjoyed reading Sir Walter Raleigh’s “History of the World” (Sir Vailter Raillis Hystorie) as well as the classics of Greek and Roman literature.

At an early age his accounts show that Montrose was unfailingly generous most notably with those who served him, as well as the poor and needy, minstrels and dancers, servants of his hosts as well as to the kirk. He donated the funds for building a new library for Glasgow University in 1631 while he was living at Kinnaird Castle with his young wife Magdalene Carnegie.(4) His early poetry written on the fly leaves of his textbooks shows that he realized that great things were expected of him, even if he did not know what they might be. On the leaf of Caesar’s Commentaries he wrote;

“Though Caesar’s Paragon I cannot be,

Yet shall I soar in thoughts as high as he.” (5)

These words show his respect for Kings and Rulers and an understanding that somehow he would eventually stand on the same world stage as they. His following words express his concept of the difference between a Sovereign and their subjects.

“Can Little Beasts with Lions roar,

And little Birds with Eagles soar;

Can shallow Streams command the Seas,

And little Ants the humming Bees?

No, no, no, no, it is not meet

The Head should stoup unto the Feet” (6)

These words were written in 1650 following his betrayal by Neil Macleod of Assynt and while he was being paraded by his captors wounded, astride a nag, dressed in peasants clothing on the way to Edinburgh. Those who came out to revile him fell silent when they saw how bravely and with what dignity he carried himself even in defeat. The fact that he could write poetry when he knew that his fate was sealed speaks volumes about Montrose’s personal conviction and his belief in his God given rights and just authority of his Sovereign.

Montrose’s chaplain, the Reverend George Wishart is the author who

can be called his biographer. Wishart is as to be expected very complimentary in his descriptions but two statements stand out as genuine. He describes Montrose as “a most resolute and undaunted spirit,” and this certainly fits the historical facts as we know them. The second involves the Irish “redshanks” that served under him. Wishart points out that there were no formal ties to him, of country, language or religion. They endured misery, suffering and death without pay from him.

Their loyalty was to Alasdair MacDonald who they called “Colkitto” which means,

“Who can fight with either hand”. (7) (8)

Yet even when MacDonald left Montrose following the Battle of Kilsyth, in early September of 1645, to take his vengeance on the Cambells, many of his Irish remained with Montrose and indeed died for him at Philiphaugh on the 13th day of September. Montrose treated these soldiers in a foreign land with kindness and consideration but with firmness that generated their respect. They recognized his dedication and bravery and saw that he led from the front and took the same risks that his foot soldiers took, he sat by their campfires at night and listened to their thoughts and concerns. The result was they would have followed him into the fires of hell if he commanded.

Some have questioned the quality of Montrose’s marriage to Magdalene Carnegie but some of his finest poetry seems to have been inspired by her.

“The golden laws of love shall be,

Upon this pillar hung,--

A simple heart, a single eye,

A true and constant tongue;

Let no man for more love pretend,

That he has hearts in store;

True love begun shall never end,

Love one and love no more.” (9)

These words from “I’ll never love thee more” leave no doubt that they speak of his feelings of love for his wife and not his loyalty to his King. Montrose was only 17 when they were married and with long periods of separation due to war, imprisonment and exile there was never any hint of extramarital relationships that were common among the aristocracy of that time. He never married after Magdalene’s death and there are no indications of romantic attachments. (10)

Charles I ‘s cold reception of Montrose when he returned from the continent had been a humiliation to Montrose. He had no idea that Hamilton had poisoned the king’s mind to protect his own interests and the result was that in spite of his love of the monarchy he returned home to side with the covenanting party in Scotland. They played on his ego and the memory of the humiliation he had experienced at Westminster. The Scottish clergy were busy arousing their parishioners to the “Threat of Episcopacy”. At the same time, Argyll was using the public upheaval to extend his already considerable power over the civil government.

As the State and Kirk began to merge into a theocracy Montrose realized the inherent danger of a dictatorship controlled by a Machiavellian Prince and a fanatical clergy. In the face of growing evidence Montrose continued to serve the Covenanters until they accused him of secretly corresponding with the King and placed him in Edinburgh Castle.

His return to loyalty to his King resulted in his excommunication by the kirk but it never diminished his faith in the old Presbyterian Kirk of his youth or even the National Covenant of which he was an early signer. Montrose’s motto, “Nil Medium”, No Middle Ground, defines his loyalty to his King over that of the of the Covenanter government of Scotland.

In a letter to a friend Montrose outlines his concept of government. He states that a civil society that is pleasing to God must have government. Government must have a Sovereign to enforce laws and direct private endeavors to public ends. The power of the Sovereign over the people is above any power on earth and cannot be rescinded. It is instituted by God for His glory and the temporal and eternal happiness of man. (11)

At the risk of sacrilege it is hard not to compare the last days of the Great Marquis to that of Jesus Christ. Supposed friends betrayed both, for money. Both were paraded before the throngs in an effort to disgrace them, which failed. Both were tried on trumped up charges before church courts. Both were calm and dignified in the face of impending death. Both were put to death like a common criminal.

Sir John Skelton described it this way, “Christendom bows humbly before the Cross. The crown of thorns has become a crown of light. No martyr ever met a meaner death more nobly than Montrose. He saw with wonderful clearness the dignity of the indignities that were heaped upon him. The halter, the scaffold, the dismembered limb, had each its noble side, on which, it represented honour, loyalty, and unspotted faith.” (12)

Today we remember Montrose, four hundred and ten years have gone by but his noble life gives us a reason to “Ne Oublie” TO NEVER FORGET.

FOOTNOTES

1 BUCHAN, John; MONTROSE; Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, London,1928; P 34.

2 BUCHAN, John; MONTROSE; Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, London,1928; P 35.

3 The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland;

http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/search/?keyword=Drygate&submit=sear ; Site Number NS66NW 147; GLASGOW, DRYGATE, DUKE OF MONTROSE’S LODGING.

4 BUCHAN, John; MONTROSE; Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, London,1928; P 36.

5 BELL, Robin Graham: Civil Warrior; Luath Press Limited, Edinburgh, 2002; P 17.

6 BELL, Robin Graham: Civil Warrior; Luath Press Limited, Edinburgh, 2002; P 91.

7 WISHART, George; MEMOIRS of the Most Renowned James Graham, Marquis of Montrose; Archibald Constable & Co., Edinburgh, 1819; P 407.

8 BUCHAN, John; MONTROSE; Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, London,1928; P 179.

9 GRANT, James; Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose; George Routledge & CO.,

London,1858; P 16.

10 GRANT, James; Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose; George Routledge & CO.,

London,1858; P 24.

11 NAPIER, Mark, Memoirs of the Marquis of Montrose; Thomas G. Stevenson, London,1856; P 281.

12 SKELTON, Sir John; The Great English Essayists; Harper & Brothers Publishers, New

York & London, 1883; P 260.